The Epic Walking Tours Greenwich Village Historic Walking Tour includes a stop at Washington Square Park and the surrounding Village neighborhood, where Henry Bergh launched the animal rights movement in the United States. The content in this article was retrieved from New York newspapers, interviews, and speeches from 1860-1872.

“To plant, or revive, the principle of mercy in the human heart” would be “a triumph … greater than the building of the Great Pacific Railroad.” – Henry Bergh

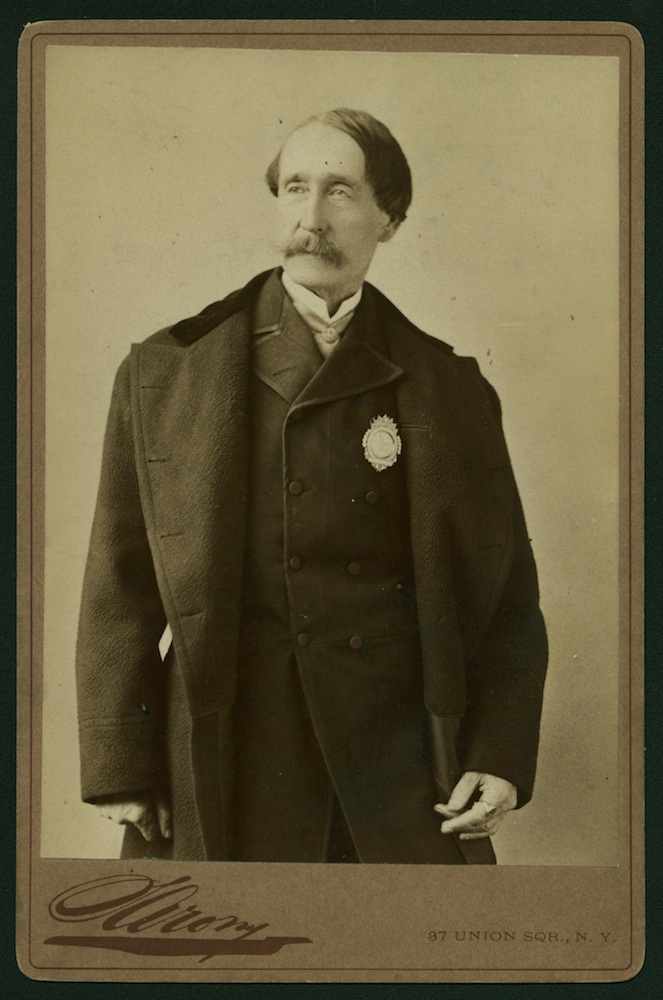

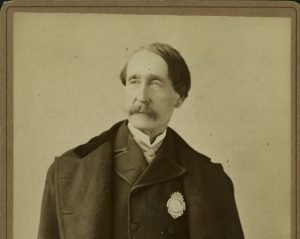

In April 1866, a well-dressed gentleman with a seasoned mustache and memorable face stood at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street near Madison Square Park in Manhattan, a few blocks north of Greenwich Village. The traffic was heavy, with horses lugging people in carriages. Suddenly, the gentleman spotted a teamster beating a horse.

“My friend,” he said, “you can’t do that anymore.”

“Can’t beat my own horse,” the teamster replied, “the devil, I can’t.”

“You are not aware, probably, that you are breaking the law,” the interloper said. “But you are. I have the new statute in my pocket, and the horse is yours only to treat kindly. I could have you arrested. I only want to inform you what a risk you run.”

“Go to hell,” yelled the teamster. “You’re mad!”

Thus began in earnest two decades of advocacy by Henry Bergh to elevate Americans’ conscience about how they treat animals and a legal effort to hold people accountable for abusing them. Hours earlier, New York legislators passed the first-ever bill that made it illegal to cause pain to animals “unjustifiably,” marking a historic step forward in protecting animals in the 19th century.

Henry Bergh’s path to becoming the country’s first national voice for animals was not something people could have seen coming.

Bergh grew up in the Village. His father, Christian Bergh, built his reputation as a brilliant pioneer in New York’s nascent shipbuilding industry. His ships helped open the city to the world during the Industrial Revolution. Henry joined the family business in 1835 and assumed the helm after his father died in 1843. By the time he exited the company, he had amassed considerable wealth, giving him influence with the country’s power brokers and politicians. He fine-dined and traveled with his wife, enjoying the opulence of a burgeoning society and all its spoils. While he intentionally built his wealth, he found his moral compass unexpectedly. It would forever change the trajectory of his life.

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Bergh as a diplomat at the court of Czar Alexander II in Russia to oversee the country’s judicial reforms. While in Russia, Bergh witnessed peasants beating their horses. “At last,” he said, “I’ve found a way to utilize my gold lace.” A “gold lace” refers to someone’s rank in society.

On his way back to New York from Russia in 1865, Bergh stopped in London. While in London, Bergh received news on April 15, 1865, that Lincoln had been assassinated. Uncertain of his future work abroad, he met with the president of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, founded in 1824. The organization’s work and the abuse he witnessed inspired Bergh to start the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) in the United States.

Bergh, an opponent of slavery like his father Christian, referred to animals as “our speechless slaves.” He hoped people would make the connection between the sentience of people and animals—both of whom he argued deserved to live a free and natural life. However, he was skeptical of people’s ability to show compassion and believed that kindness toward animals would be more effectively achieved by passing and enforcing laws to protect them.

And so he did that.

On a cold evening on February 8, 1866, two months before the formation of the ASPCA, Bergh delivered a speech on the importance of protecting animals at Clinton Hall in the Village. Clinton Hall was a library in the former Astor Place Opera House at 21 Astor Place. It had its own subway stop, the closed entrance of which remains in the present-day Astor Place subway station, which reads, “Clinton Hall.”

In addition to Bergh’s speech, Clinton Hall became known for hosting lectures from Ralph Waldo Emerson, Frederick Douglas, and Mark Twain in later years. It was also the site of the Shakespeare Riots, an 1849 brawl that resulted from a dispute over who should perform Hamlet and Macbeth—American-born citizens or their colonial overlords.

Bergh unveiled his plan to the mayor and other dignitaries at Clinton Hall. In the historic speech, he offered insight into the brutal confinement, abuse, and slaughter of animals, including New York City’s horses. Bergh said, “This is a matter purely of conscience. It has no perplexing side issues. It is a moral question in all its aspects.”

On February 12, 1866, the New York Daily Herald wrote about Bergh’s compelling presentation at Clinton Hall. They reported that Bergh spoke about his concern that people laughed at the killing of animals in the Roman amphitheater. He dwelt on the bullfights of Spain and the modern physiologists of Paris for their blood-chilling cruelties under the name of vivisection. He appealed to the city and the country to join him in opposing suffering and torture.

Support came in droves from the well-connected. New York Mayor John Hoffman, inventor and philanthropist Peter Cooper, businessman John Jacob Astor Jr., publishers John and James Harper, attorney James T. Brady, bibliophile James Lenox, and educator Ezra Cornell signed on. Within five years, 19 states created an ASPCA chapter and began enforcing laws.

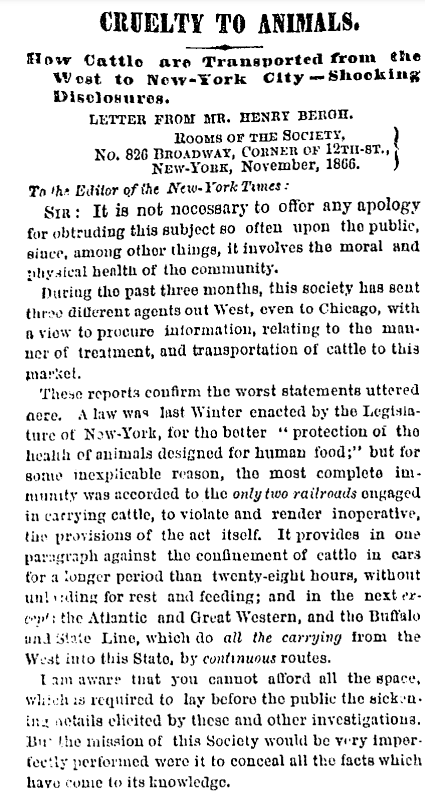

The ASPCA opened its headquarters in a house where a building now stands at 826 Broadway south of Union Square, a few blocks north of the Village. The bottom floor is home to the well-known Strand Bookstore.

Shortly after creating the ASPCA in April of 1866, New York legislators passed the nation’s first anti-cruelty law for animals at Bergh’s request and empowered the organization to enforce the law. The ASPCA law enforcement agents, known as “Berghsmen,” pursued people abusing horses and livestock, but also dogs and other animals confined and tortured at the hands of a society that showed little mercy for the most defenseless among them.

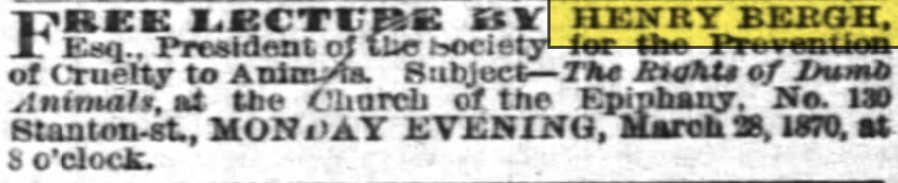

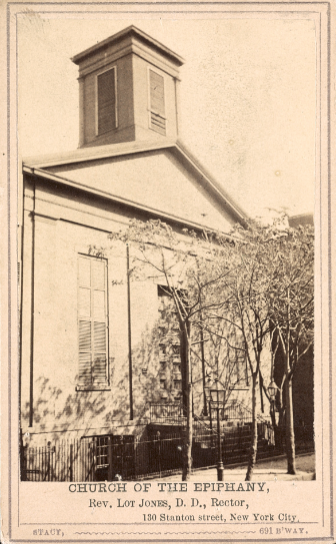

In addition to enforcing the law, Bergh spent years speaking to anyone who would listen about the moral importance of showing compassion for animals, frequently giving free speeches at churches, union halls, political events, and other public gatherings.

Three blocks east of Washington Square Park on Broadway and 4th Street, Bergh rented an office to enlist support for the ASPCA and new laws that protected animals. He made his first arrest when he spotted a man transporting roped calves with their heads hanging off the side of a carriage getting hit by passersby. In the following years, Bergh spent his time in the courtroom as a prosecutor of animal abusers, lobbying legislators, raising money for the ASPCA, and writing op-eds in New York’s newspapers.

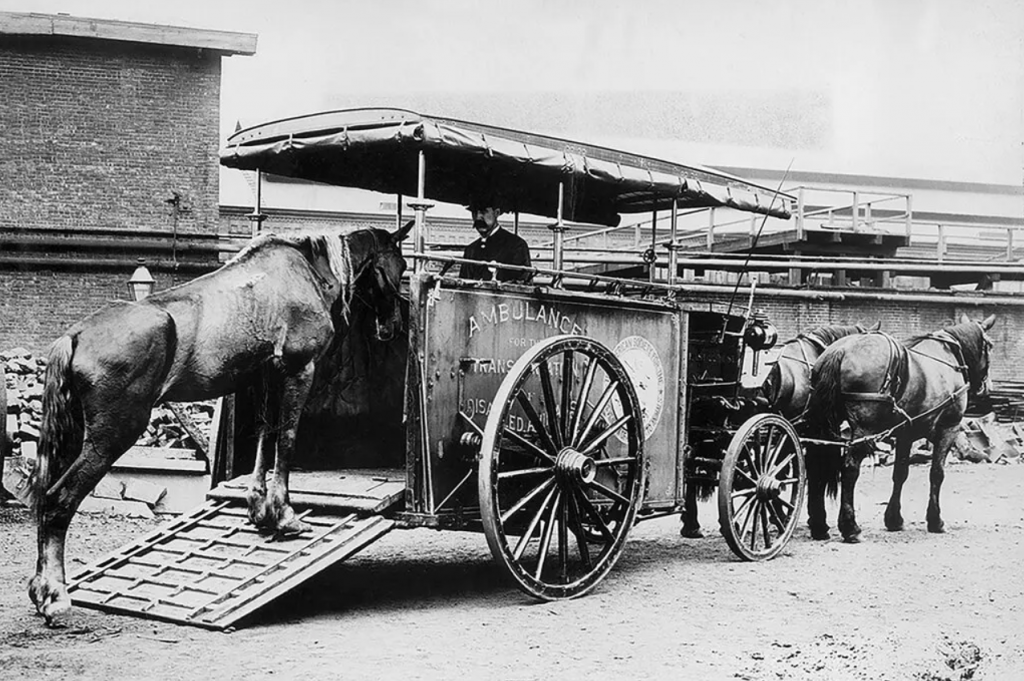

He quickly became known in the city and beyond its limits as the most determined, fearless, and influential supporter of animals. One winter evening, with the streets filled with snow and slush, Bergh ordered every sick and injured horse off the street, forcing crowds of New Yorkers to walk as it created a logjam. His public disputes with New York City circus owner P.T. Barnum over feeding live rabbits to snakes for entertainment drew national attention. Determined to help animals most in need of care, Bergh created the first ambulance for sick and injured horses in 1877.

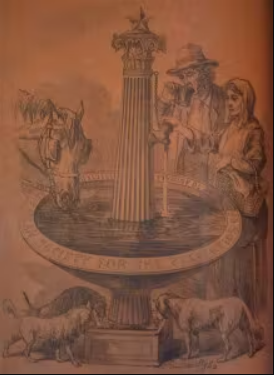

Bergh’s concern over dehydrated horses being overworked in the heat prompted him to install drinking fountains throughout the city. The first fountain in Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village was established to hydrate horses.

In 1874, the case of “Little Mary Ellen” Wilson, a ten-year-old abused child, inspired Bergh to create the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, which became the first organized movement for the protection of children in the world. No laws existed at the time to protect abused children, so Bergh used the ASPCA’s animal protection laws to cover children, arguing that they should have the same right to protection from abuse. The organization’s work continues today.

Bergh died on March 12, 1888, in New York City. Friends and family laid him to rest at Green-Wood Cemetary in Brooklyn. His archnemesis, P.T. Barnum, attended his funeral, evidence of the respect even his foes had for his advocacy.

Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a eulogy at this passing:

“That man I honor and revere

Who without favor, without fear,

In the great city dares to stand

The friend of every friendless beast,

Among the noblest in the land,

Though he may consider himself the least.

And tames his unflinching hand

The brutes that wear our form and face,

The were-wolves of the human race.”

Andrew Kirschner is a licensed New York City sightseeing tour guide. He founded Epic Walking Tours, which offers historic walking tours in Greenwich Village.

4 Responses

This is such an inspiring story of bravery and compassion. Thank you for sharing it with us.

Awesome story. We need more people like like Henry Bergh in the world. Animal need to be protected.

Very nice blog, Andrew. Thank you. Here’s my review of the Bergh’s biography, Traitor to His Species:

https://paulshapiro.medium.com/technology-to-animals-rescue-a-book-review-of-a-traitor-to-his-species-548b0fa9bbea

That was so well-written Andrew….an illuminating synopsis of a remarkable life! Souls as transparent, empathetic and noble as Henry Bergh’s have appeared all over the world , all across the millenia, and to be sure most of them died in obscurity , their noble deeds unrecognized and unrewarded. It’s souls like Henry Bergh’s and the many like him who have come and gone, who have tried, each in his/her own time/place…. with their limited human power/resources…. to reduce the suffering of voiceless innocents on this planet…it’s souls like these that, while falling far short of “restoring my faith” in humanity , inspire me to keep fighting always, for the sentient creatures sharing the planet with us….and to never give up!!!

thank you for sharing the story of a unique, extraordinary life – a true nobleman, iconoclast and hero – with us and with the world.