The Epic Walking Tours Greenwich Village Variety Walking Tour visits Washington Square Park. The historical content in this article was retrieved from New York newspaper articles from 1819 and digital archives from the New York Public Library.

Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village, New York, was not always filled with musicians, artists, bird feeders, chess players, tourists taking photos, and NYU students studying and sunbathing. The Indigenous Lenape occupied the land for generations until the Dutch arrived in 1609. The British followed suit in the 1860s until they outstayed their welcome with colonists. The city purchased the land in 1827 and turned it into a public park.

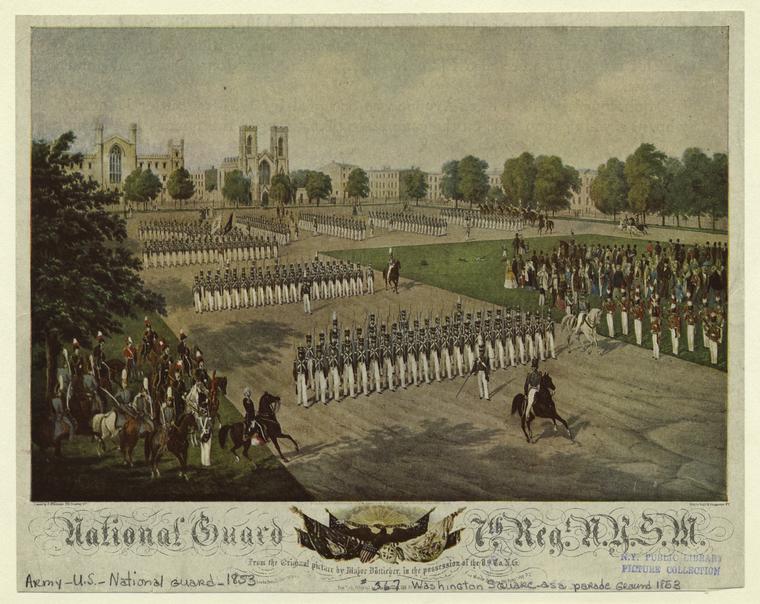

Before the park’s construction and transformation into a mecca for bohemians, trailblazers, and advocates in the 20th century, Washington Square Park served as a military parade ground in 1826. Prior to hosting military drills, it was a burial ground, known as a “Potter’s field,” that provided a final resting place for poor New Yorkers since 1797. During this time, the city also used the land for public executions. The gallows stood around the location of the Washington Square Arch, which was constructed in 1892.

The story of the “Hangman’s Elm,” which stands on the park’s northwest corner, draws its legend from this era. Folklore suggests Patriots hanged traitors from its branches during the American Revolution in the 18th century, although no evidence exists that people hung from the Bronze Age ancestor. The tree is the oldest known in Manhattan, though, tracing back to about 1690, when the British occupied the land and New Netherland became New York.

There is only one recorded execution in present-day Washington Square Park.

On July 13, 1819, thousands converged on the park to witness it. It was such a spectacle that an overflow crowd stood on nearby rooftops and watched out windows. A dark hour in New York’s storied history, people reviled and celebrated the execution on the streets of Greenwich Village.

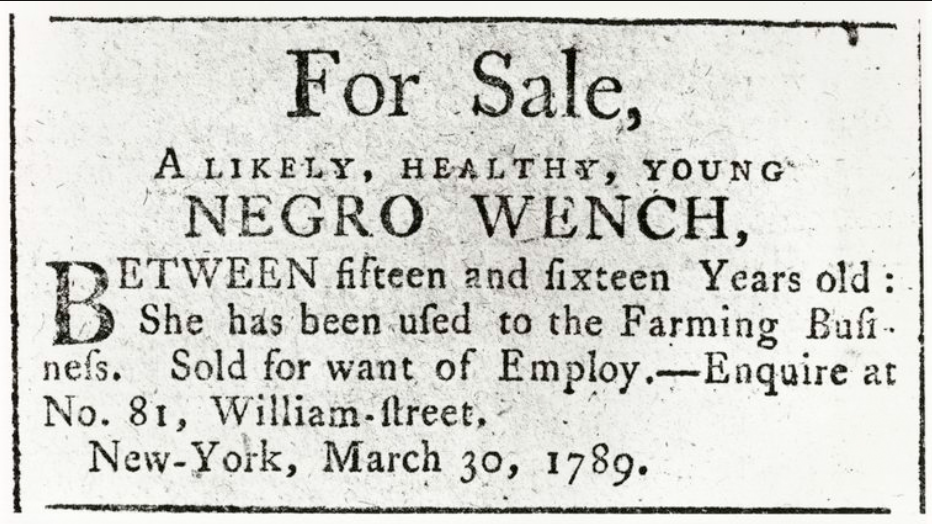

At only 36 years old, the United States had not fully aligned its actions with its values. As New York industrialized, many enslavers moved to New York from the South, bringing their slaves with them. White New York residents recognized the hypocrisy of maintaining the institution of slavery on the heels of the war’s cause of independence. Thus, New York abolished slavery in 1817, but the last New York slave did not gain freedom until 1827.

Thus, in 1819, not everyone had gained independence in New York.

Born into slavery in Mount Pleasant, New York, in 1799, Rose Butler never knew freedom. Several people owned her during her lifetime. Manhattan resident William Morris bought Rose in 1817. The historical records indicate that their relationship was understandably tenuous, which likely caused her to revolt. In 1819, she set the Morris house on fire. Although she failed to burn it down, an arson conviction succeeded, which the New York Supreme Court upheld.

A judge sentenced Rose to death by hanging. In 1796, New York abolished the death penalty for crimes other than murder and treason. Arson was added as a capital crime in 1808 since it posed a danger to neighboring families in the city, given the absence of fire extinguishers and a fire department that could respond in time.

In 1819, New York’s Evening Post described Rose’s demeanor upon her interrogation as “rude and offensive” but made no mention of the behavior of Mr. Morris, the man still enslaving her.

On July 13, 1819, the local sheriff brought Rose Butler to the gallows of the Potter’s field in present-day Washington Square Park. Minutes before appearing, she asked for a drink of water. Her friends arrived in a carriage, commiserating about her impending death.

After the governor refused final pleas for a pardon, the sheriff, whom The Alexandria Gazette described as “firm and dignified” in his manner, placed a rope around Rose’s neck, hanged the 19-year-old, and buried her body unceremoniously beneath the field. The Gazette wrote, “We hope she has repented, and went into eternity in a pardon-asking mood.”

In one of the most memorable final acts in American history, Rose spoke her last words: “I am satisfied as to the justness of my fate—it is all right.”

Shortly after Rose Butler’s death, a poem appeared on a bench near the site of her hanging:

Rose Butler sat upon a bench —

Down drop’t the trap and hanged a negro wench

Visit Epic Walking Tours on Facebook for a video of Rose Butler’s story filmed in Washington Square Park.

Andrew Kirschner is a licensed New York City sightseeing tour guide and the founder of Epic Walking Tours, which offers historic walking tours in Greenwich Village.