Epic Walking Tours’ Historic Village Walking Tour stops at two locations with direct ties to Alexander Hamilton. The information in this story is sourced from New York newspapers from 1804 and the New-York Historical Society, New York’s first museum, which was founded the same year Hamilton died.

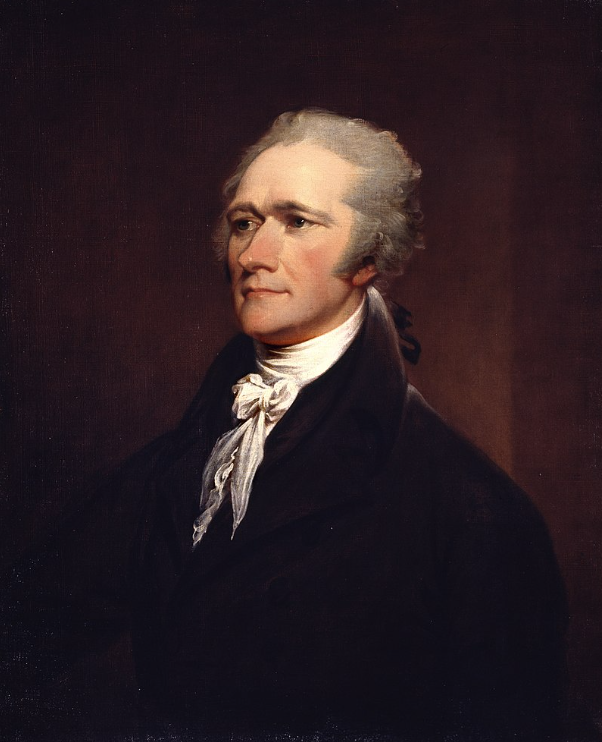

Alexander Hamilton died in Greenwich Village on July 12, 1804. A gunshot wound ended his life 47 years after it began. His legacy survived.

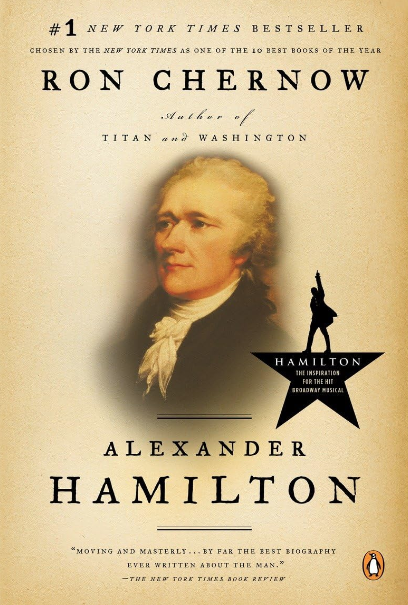

The story has long been a part of the American experience, told by high school American History teachers for generations and more recently narrated by Ron Chernow in his book Alexander Hamilton and Lin-Manuel Miranda on Broadway.

Hamilton was a Federalist, a political party that originated under George Washington’s first administration. Federalists believed in ratifying the U.S. Constitution, a strong union and centralized federal government with a central bank, the separation of powers through three branches of government to protect people’s rights, and weaker state governments. The Federalists saved the country from financial ruin during its formation.

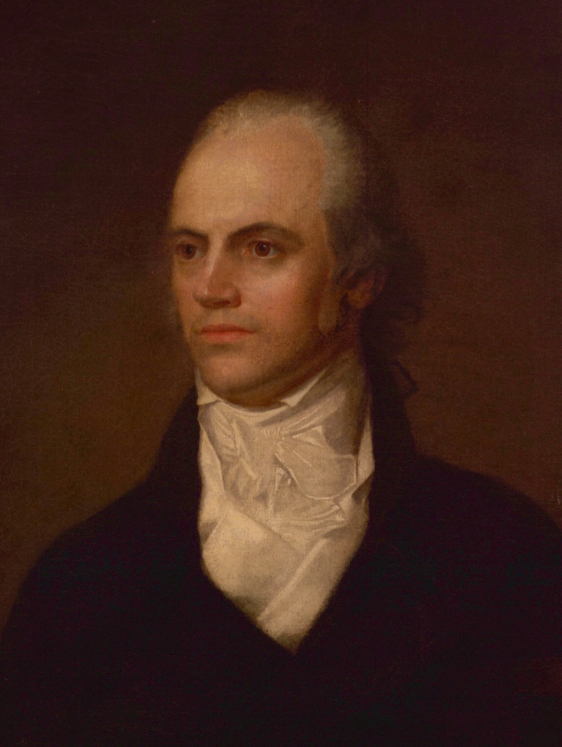

Burr was a Jeffersonian Republican (also referred to as a Democratic-Republican), although he kept political parties at arm’s length. This is not the same party as the modern-day Republican Party. The Democrat and Republican parties evolved from the Jeffersonian-Republican Party. Jeffersonian Republicans believed in decentralizing the federal government, free markets, and free trade.

Burr and Hamilton clashed for years over political seats and policies. Burr published a critical document Hamilton authored about Federalist President John Adams in 1800 that was not intended for public circulation. It caused a rift in the Federalist Party.

Hamilton supported Thomas Jefferson over Aaron Burr when they tied in presidential balloting, and opposed Burr again in 1804 when he ran for governor of New York.

But it was Hamilton’s remarks at a city tavern dinner party in February 1804 during which he criticized Burr that pushed the Vice President to silence his rival. On April 23, 1804, New York Republican Charles Cooper published his account of Hamilton’s words from the party.

Cooper claimed Hamilton called Burr “a dangerous man, and one who ought not be trusted with the reins of government.” He added that Hamilton also expressed a “more despicable opinion” of Burr. It was a bridge too far for Burr, who blamed Hamilton for his loss in the governor’s race.

Dueling had its roots in the Middle Ages, hundreds of years prior. Americans adopted the practice to defend their honor. Advertisements for upcoming duels were posted on street corners and in taverns. If a politician ignored a challenge, it could destroy their career. Politicians and newspaper editors lost their lives over character disputes.

Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel to restore his honor following his public statements. Hamilton could retract his words and apologize or duel. He said he could not apologize for sentiments he intended and thus opted into the duel. Although dueling was common during the Revolutionary War era, it typically ended with shots fired into the air. Burr’s animus did not allow for such an exercise of restraint.

The rivals chose New Jersey to settle their differences because the state carried lighter penalties for the practice that was becoming more frowned upon in the North. Dueling was illegal in New York in 1804, but still tolerated in its neighboring state. Hamilton predicted that the duel might end badly, and thus made preparations for his demise and bid farewell to his wife.

The men faced off on July 11, 1804, at Weehawken. Hamilton fired his shot into the air; Burr made a direct hit. Hamilton fell to the ground.

William Bayard was a prominent New York City banker and close Hamilton friend who lived in Greenwich Village. Bayard’s ancestors arrived in the Dutch colony when Peter Stuyvesant ruled it. One of the largest landowners in New York, the Bayards were also descendants of the Schuyler family. Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler in 1780.

After Hamilton was shot, Bayard met the boat that carried him across the river to New York and escorted him to his home for medical care, a common practice at the time.

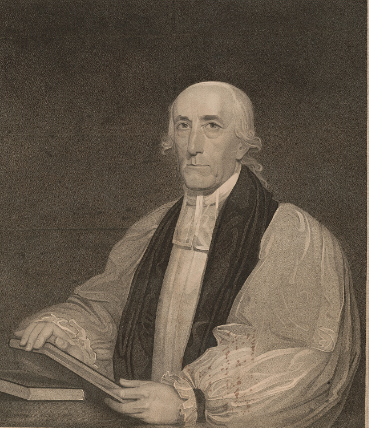

On Thursday evening, July 12, 1804, the day after Aaron Burr shot Alexander Hamilton, Reverend Benjamin Moore, Bishop of the protestant episcopal church in the state of New York, visited Hamilton at Bayard’s home at Hamilton’s request. Hamilton had only hours left to live when Moore arrived.

Reverend Moore wrote a letter to the New York Evening Post on July 12, 1804, the evening of Alexander Hamilton’s death. Moore stated that he wanted to ensure that the public had the facts about Hamilton’s final hours between the time of his duel and “his departure out of this world.”

Moore wrote, “Yesterday morning, immediately after he was brought from Hoboken to the house of Mr. Bayard of Greenwich Village…” This statement confirms that Hamilton spent his final hours in the Village, an ironic end given some of the events that transpired only blocks away, which you can learn about on the tour.

Mr. Moore wrote that he received notice of the “sad event” and “a request from Mr. Hamilton” that he administer “the holy communion.”

Upon approaching his bed, Moore wrote that Hamilton said to him, “My dear sir, you perceive my unfortunate situation and no doubt have been made acquainted with the circumstances which led to it. It is my desire to receive the communion at your hands.”

As he was receiving his communion, Hamilton said, “I have no ill-will against Colonel Burr. I met him with a resolution to do him no harm—I forgive all that happened.” Moore wrote that he had “no reason to doubt his sincerity.” Soon thereafter, Hamilton “expired without a struggle—almost without a groan,” Moore wrote.

Moore concluded his letter with a criticism of dueling, which he stated has “deprived his friends of a beloved companion, his profession of one of its brightest ornaments, and his country of a great statesman and a real patriot.”

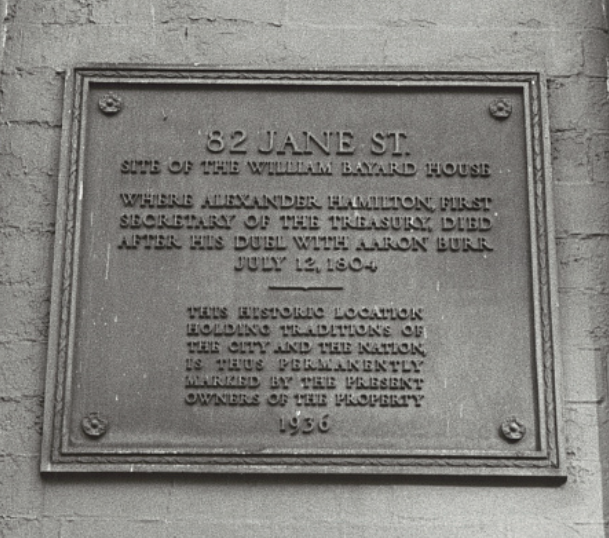

Moore’s letter on the day of Hamilton’s death confirms that he died at William Bayard’s home in the West Village. The exact location of the Bayard home in the Village remains subject to debate. Most history books record it as 82 Jane Street, although the plaque erected at that location by the building’s owner in 1936 likely does not mark the exact location. Historical records indicate Bayard had a home on nearby Horatio Street in the Village. The current structure on Jane Street was built in 1886, about 82 years after Hamilton’s death, so even if it was the location of Bayard’s house, it is not the actual house.

A 1767 map shows Bayard’s house below present-day Gansevoort Street on the north side of Jane Street, which likely places it on present-day Horatio Street. Although historians cannot mark the exact spot of Hamilton’s death, Hamilton is buried at nearby Trinity Church in the Financial District.

Newspapers recorded that not since the death of George Washington in 1799 did the country mourn with such grief. When he died, he was one of the few friends of George Washington left alive. Reports honored his bravery at York Town, unmatched legal skills, and contributions to the establishment of the country.

Burr was convicted of a misdemeanor dueling charge, which resulted in him losing his right to vote, practice law, or hold public office for 20 years. Ironically, Burr’s murder of Hamilton caused the citizenry to ostracize him for the rest of his life. The honor he sought in avenging Hamilton forever eluded him.

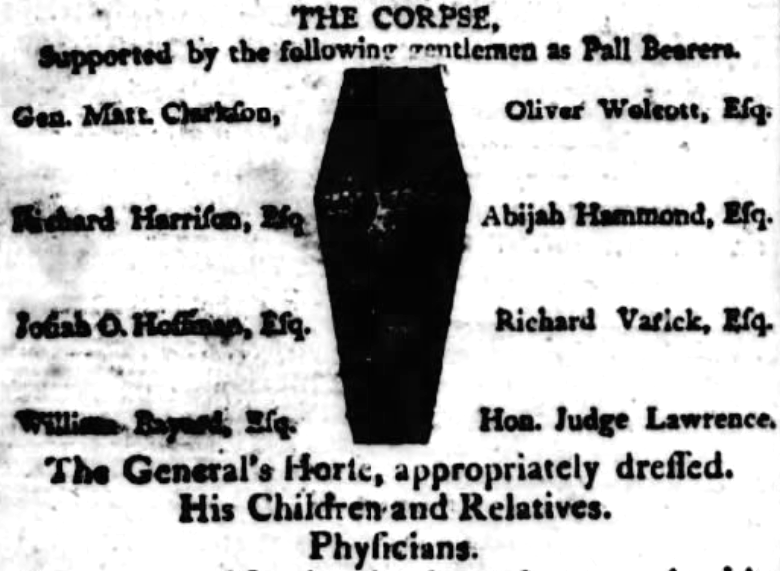

According to local newspaper reports from July 26, 1804, days after his death, Hamilton’s coffin was marched up Broadway. Thousands of people lined the streets weeping. Draped atop his coffin were Hamilton’s hat and sword with his boots along the side.

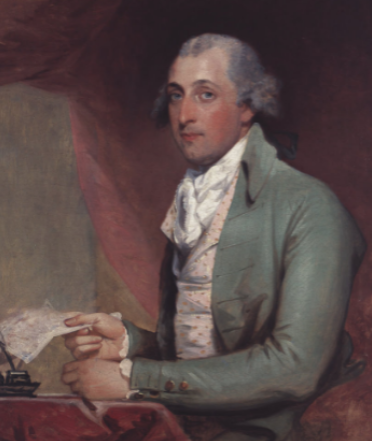

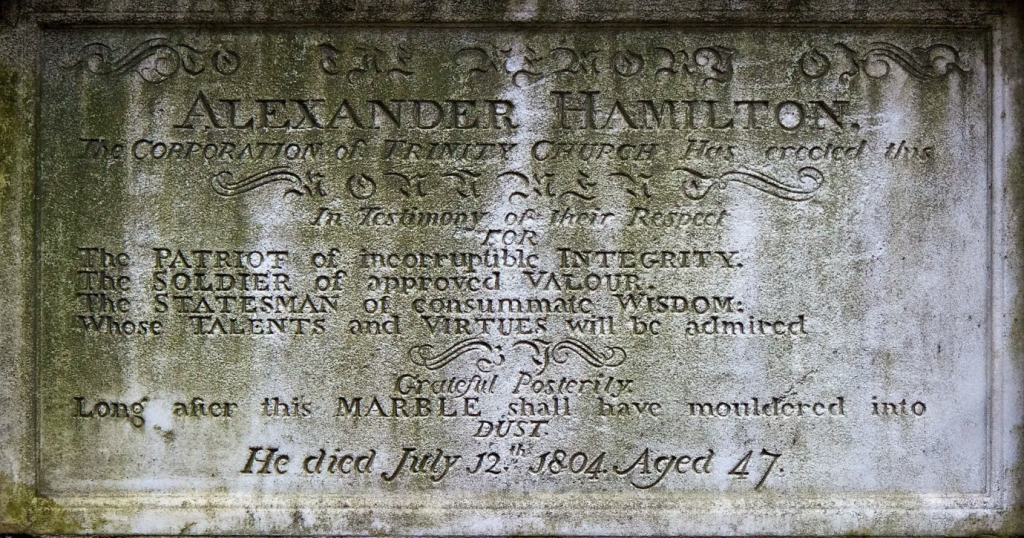

Gouverneur Morris, an American statesman, a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution, and the author of the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, delivered the eulogy for Hamilton at Trinity Church. Hamilton’s four sons stood by his side—the eldest 16 and the youngest only six years old. Morris recounted Hamilton’s journey from obscurity to the Revolutionary War to helping mold the United States.

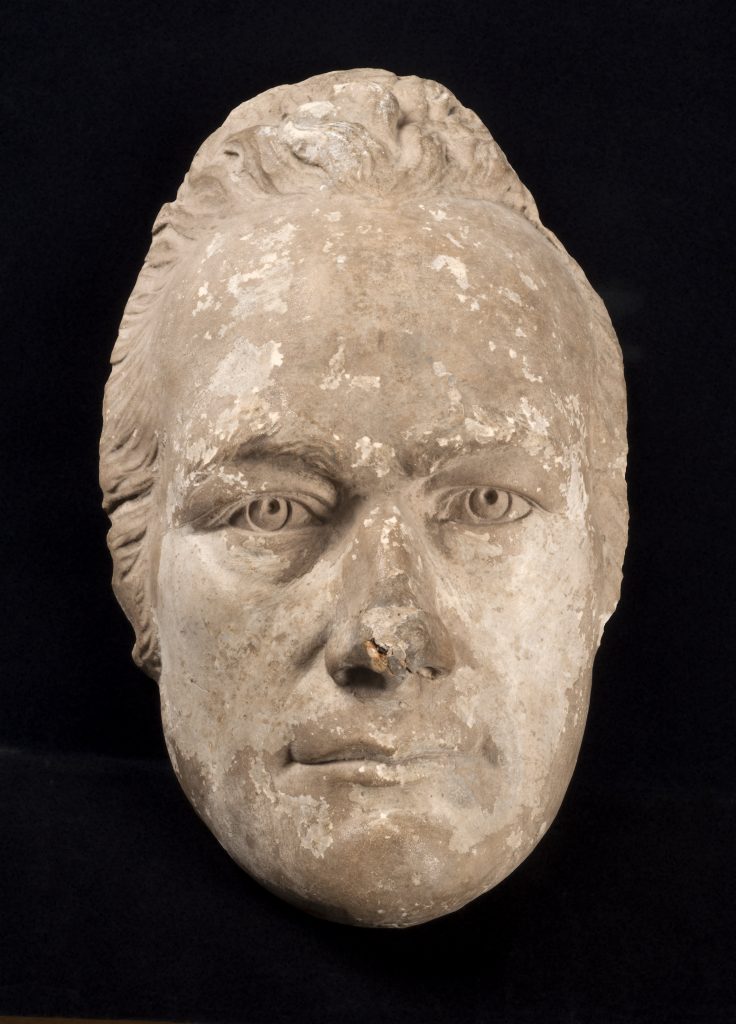

Aaron Burr killed Alexander Hamilton in his forty-seventh year with decades of vision ahead of him, yet Hamilton still forgave him. The public would be much less forgiving. A death mask of Burr housed at the New-York Historical Society shows the long-drawn face of a man who had endured the wrath of the public in the 32 years that followed until he died in 1836 at age 80.

In his short life, Hamilton made a lasting impact. As a founding father of the United States, he helped draft the U.S. Constitution, fought heroically in the American Revolution, created the first U.S. monetary system, served as the first Secretary of the U.S. Treasury, established the federal tax system and National Bank, and fought to end slavery. Hamilton’s death mask shows a man in the prime of his life.

One of the great mysteries remains the final advice he offered his children, who stood at his bedside during his last moments. His eldest son Philip died three years earlier at 19, defending his father’s name in a duel in New Jersey.

Although Hamilton did not survive a gunshot wound from his rival, his impact endures.

Andrew Kirschner is a licensed New York City sightseeing tour guide and the founder of Epic Walking Tours, which offers historic walking tours in Greenwich Village.