Epic Walking Tours visits the “Aaron Burr House 1802” in Greenwich Village.

On the misty morning of July 11, 1804, Aaron Burr, the sitting Vice President of the United States, fatally shot former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton in a duel on the cliffs of Weehawken, New Jersey. The encounter was the culmination of years of political rivalry and personal animosity, but its outcome did far more than resolve a private grievance—it detonated Burr’s political career, reshaped public memory, and cast him as one of the most controversial figures in early American history.

Though Burr emerged from the duel legally unscathed, he spent the rest of his life navigating the wreckage of his reputation. His trajectory after 1804 is one of remarkable contrasts: a man once at the center of the young republic reduced to exile, disgrace, and near-total obscurity.

The Duel and Its Immediate Consequences

By 1804, Hamilton’s influence had waned, but his public standing remained strong in Federalist-dominated New York. Hamilton had returned to private law practice after leaving government, and his reputation as a brilliant constitutional thinker and financial architect still commanded national attention. He was one of the few figures in early American politics who was deeply polarizing and widely admired.

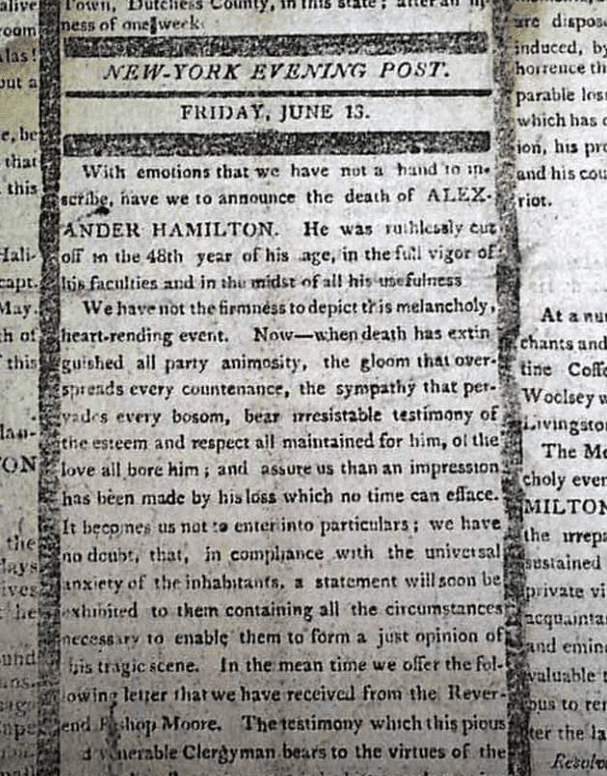

Hamilton’s killing stunned the public. While dueling was not uncommon among elite men of the era, the idea that a sitting Vice President had killed a former cabinet secretary seemed to many Americans a grotesque overstep. Public mourning was widespread, especially in northern cities. Newspapers and pulpits denounced Burr. Church bells tolled across New York, and Hamilton’s funeral became a civic event, cementing his martyrdom.

Burr, on the other hand, faced two indictments—one in New York, one in New Jersey—for murder. He fled south to avoid prosecution but was never arrested or tried. The charges quietly faded over time, but the damage was irreversible. Politically, Burr was finished. His name became synonymous with ambition gone awry.

Burr’s Feelings About Killing Hamilton

Burr rarely spoke publicly about the duel after it occurred. He offered no apology, no explanation. To some, his silence implied coldness; to others, it suggested deep regret too difficult to articulate. Accounts from later years indicate that while Burr was not haunted by guilt in a conventional moral sense, he understood that killing Hamilton had been a political catastrophe.

He may have believed that the duel would salvage his honor or end Hamilton’s personal attacks on his character, but he underestimated the public’s response. Unlike Hamilton, who reportedly fired into the air, Burr shot to kill. The asymmetry—intentional or not—cast Burr in a darker light.

Later in life, when asked directly about the duel, Burr often responded evasively or changed the subject. Though he never expressed remorse, he seemed to recognize that it had been a personal turning point from which he never fully recovered.

Jefferson’s View of Burr and Hamilton

Thomas Jefferson distrusted both men but in distinct ways. He detested Hamilton’s monarchist sympathies and centralized fiscal policies but respected his intellect and consistency. Burr, on the other hand, was more personally troubling to Jefferson. He saw Burr as a schemer, a man whose ideology bent in whichever direction served his ambition.

By 1804, Jefferson had already decided to exclude Burr from his re-election ticket, replacing him with George Clinton. The duel gave Jefferson additional cause to distance himself. While he did not publicly condemn Burr in the aftermath, his actions spoke volumes. He kept the Vice President at arm’s length, offered him no protection, and later, when Burr was implicated in a conspiracy to raise a private army and carve out territory in the American Southwest, Jefferson actively pursued charges of treason against him.

Jefferson’s relationship with Hamilton was fraught, but with Burr it became overtly hostile. The treason trial in 1807 marked the final rupture: Jefferson, as president, pressured prosecutors and publicly insisted on Burr’s guilt, even before the trial concluded.

The Treason Trial and Burr’s Exile

After leaving office in 1805, Burr launched what became known as the “Burr Conspiracy.” His plans remain ambiguous—whether he sought to create an independent republic in the Southwest, incite war with Spain, or simply reclaim relevance is still debated. Whatever the aim, Burr’s movements alarmed the Jefferson administration.

In 1807, he was arrested and tried for treason in Richmond, Virginia. Chief Justice John Marshall presided. Though Jefferson pressured for conviction, Burr was acquitted due to insufficient evidence. The trial, however, effectively ended any hope of a political resurrection.

Disgraced and broke, Burr sailed to Europe in 1808. For several years, he wandered through England, France, and Sweden, attempting to garner support for new schemes—none of which materialized. Often living under aliases, he struggled with debt and relied on loans from a dwindling circle of acquaintances.

Return to America and Final Years

Burr returned to New York in 1812, under an assumed name. By this point, the indictments from the duel had lapsed, and he resumed a modest legal practice. Though no longer a central figure in national affairs, Burr remained active in legal and commercial circles, albeit with limited influence.

During this time, he moved among various boarding houses in New York and eventually settled in Staten Island. In 1833, he married Eliza Jumel, but the union quickly soured, and she filed for divorce—on the grounds of Burr’s infidelity and financial mismanagement. The divorce was finalized on the day Burr died: September 14, 1836.

The Aaron Burr House in Greenwich Village

One of the more persistent myths surrounding Aaron Burr in Greenwich Village centers on the Federal-style townhouse at 17 Commerce Street, often called the “Aaron Burr House.” While the name suggests a personal connection, the truth is more nuanced. The house was constructed in 1830, well after Burr had ceased to own property in the area and some years following his political and personal downfall. However, Burr did own the land beneath it, likely around 1802, which is the date featured on a commemorative plaque affixed to the facade. Though he never lived there, the building’s association with Burr has endured, transforming it into a symbolic anchor for his lingering presence in the city’s cultural memory.

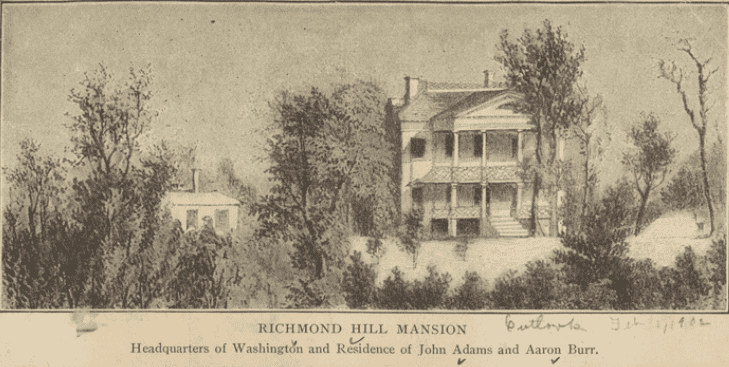

During his most prominent years in New York, including the time of his infamous 1804 duel with Alexander Hamilton, Burr’s principal residence was the Richmond Hill estate. This mansion was located near what is now Varick and Charlton Streets, in an area that sat on the western edge of Greenwich Village. Richmond Hill had a storied past: it had once served as George Washington’s headquarters during the Revolutionary War, and later, as the vice-presidential residence of John Adams. Burr acquired the estate in the late 18th century, but following his political disgrace and financial decline, he was forced to sell it to John Jacob Astor. Astor subsequently subdivided and developed the land into commercial lots, signaling the end of Richmond Hill as a residential estate. The mansion was eventually demolished, though the area around Charlton, King, and Vandam Streets preserves some architectural memory of its era.

Beyond Richmond Hill, Burr engaged in several real estate transactions in the vicinity of the modern West Village. One notable instance occurred in 1802, when he sold a plot on Locust Street to Anthony Bowrosan, as documented in property records from the time. Locust Street is now known as Sullivan Street, which runs south of Washington Square Park. These deeds and leases are preserved in the NYU Special Collections, particularly within the Astor family papers, and include a revealing 1803 lease assignment from Burr to Astor. These documents confirm Burr’s active involvement in shaping the urban landscape through property sales and development. Supporting this transaction, the New York Public Library’s Aaron Burr Papers include a wide range of letters and legal documents signed by Burr between 1780 and 1835, many of which pertain to land dealings, further evidencing his ties to the neighborhood.

While Locust Street no longer exists by that name, it once ran through what is today a densely layered part of the West Village. The general vicinity of Burr’s landholdings overlaps with streets like Sullivan Street, Barrow Street, Bedford Street, and Commerce Street, where the present-day Cherry Lane Theatre now stands. The disappearance of Locust Street from modern maps is a product of 19th-century urban development, as the grid was formalized and the rural paths of the early city were renamed or rerouted. Nevertheless, these former parcels of land once tied to Burr remain embedded in the fabric of the neighborhood, illustrating his historical imprint on this storied Manhattan district.

A Legacy of Ambition and Ambiguity

Aaron Burr’s post-duel life defies simple moral lessons or tidy narrative arcs. His decline was not merely a result of killing Hamilton but the culmination of a career shaped by ambition unmoored from lasting alliances or principles. He was, in many ways, a modern figure trapped in a nascent political system that had no room for his brand of pragmatism and opacity.

If Hamilton’s legacy was immortalized in death, Burr’s was obscured by survival. He lived three more decades, long enough to witness his own erasure from the story of America’s founding. And yet, he remained, a figure both elusive and emblematic—an object lesson in the costs of overreach, and the silence that follows a shot heard ’round the Republic.