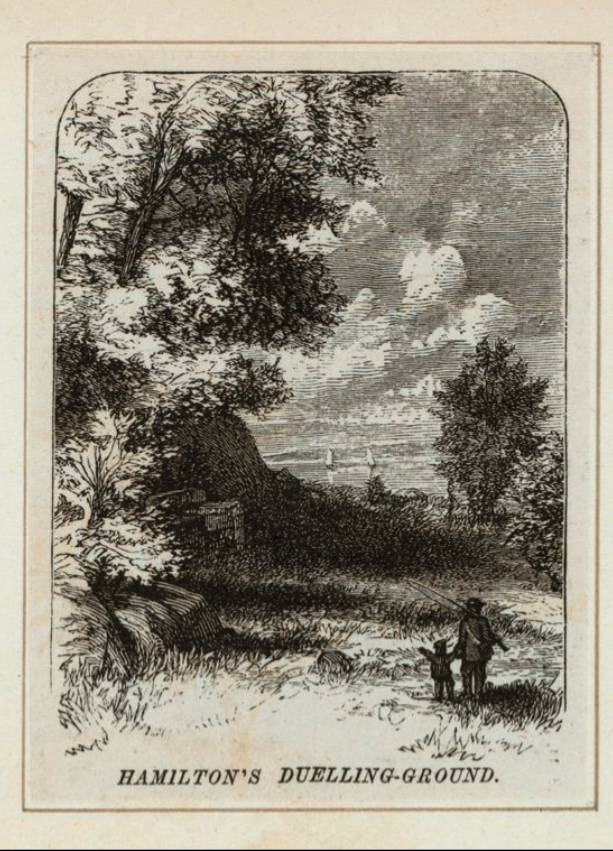

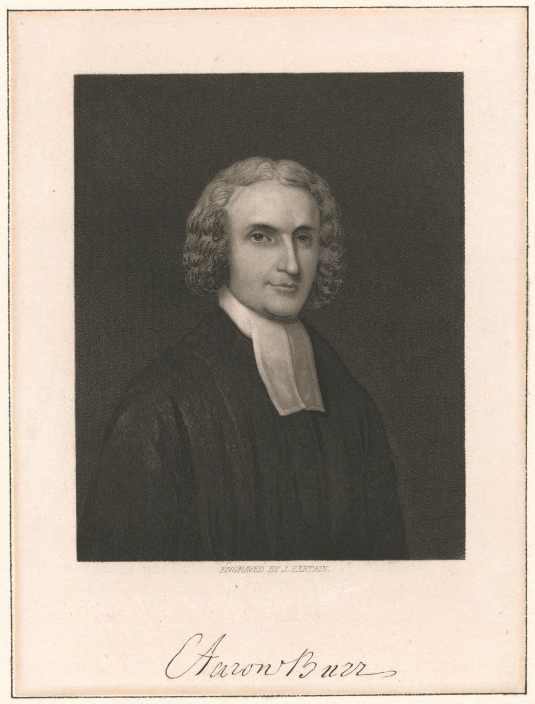

On July 11, 1804, Aaron Burr stood on the dueling grounds of Weehawken, New Jersey, and fatally shot Alexander Hamilton—former Treasury Secretary, Federalist leader, and Burr’s long-time political rival. The pistol’s crack echoed across the Hudson River and into American history, sealing Burr’s reputation as a villain in the nation’s founding drama. But the duel, though final for Hamilton, marked a strange and unfinished beginning for Burr.

Though he walked away from the killing legally unscathed—dueling was illegal in New York but tolerated in New Jersey—Burr returned to New York City a man forever altered. Once the nation’s third vice president and a brilliant legal mind, he spent the rest of his life dodging disgrace, criminal charges, and near-total obscurity. And yet, even in defeat, Burr never stopped trying to regain power. His story after the duel is one of shadows, reinvention, exile, and a final return to the city that shaped—and ultimately shunned—him.

A Political Pariah in the City He Once Ruled

After the duel, Burr’s immediate future in New York was precarious. Public opinion turned swiftly and ferociously against him. Hamilton, lionized in death, became a martyr of Federalism and constitutional order. Burr, already politically isolated, found himself facing murder indictments in New York and New Jersey, although they were eventually dropped.

Still technically vice president under Thomas Jefferson, Burr remained in Washington for the rest of his term, but his power had evaporated. By 1805, with no political future in sight, Burr returned to New York City, once the base of his operations as a feared and brilliant attorney. He resumed his law practice—but clients were scarce.

Burr lived at various times on Nassau Street in the Financial District and in rented lodgings near the city’s legal and financial center. Once a prominent figure on Broadway and Wall Street, he now moved quietly through the streets. Former friends avoided him. Political allies abandoned him. Newspapers referred to him not as “Colonel Burr” but as “the infamous slayer of Hamilton.”

And yet, Burr never appeared ashamed.

He described Hamilton’s death not as a tragedy but as the unavoidable climax of a political war. In letters, he remained convinced that Hamilton’s “monarchical” tendencies had been dangerous. He even attended some social functions in the city where portraits of Hamilton hung on the walls, unfazed.

The Western Schemes and Treason Charges

By 1806, Burr’s ambitions turned westward—literally. Believing his time in the East was over, he left New York and traveled across the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, attempting to raise a private military force. His precise intentions remain debated by historians: some believe he aimed to conquer Spanish territory in Mexico, others that he wanted to carve out a separate nation in the western U.S. frontier.

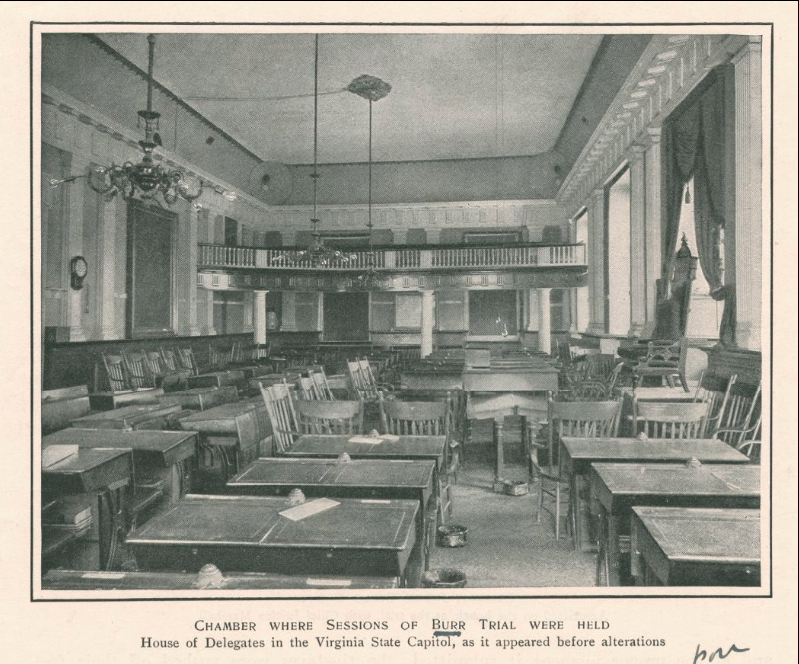

Regardless, President Jefferson accused Burr of treason. He was arrested in 1807, shipped in chains to Richmond, Virginia, and tried in a sensational federal case presided over by Chief Justice John Marshall.

Burr was acquitted—no overt act of war could be proven—but his public reputation was obliterated. Once again, he returned to New York in disgrace.

Exile and the Long Road Back

In 1808, with debts mounting and enemies everywhere, Burr left New York again—this time for Europe. He wandered the capitals of Britain, France, and even Sweden, lobbying Napoleon’s government to support his grand western schemes. No one took him seriously. For four years he lived in near-poverty, writing coded letters home, adopting false names, and fleeing creditors.

When he returned to New York City in 1812, it was as a ghost of his former self. He resumed his legal practice under a new name—Edward Charles—and lived modestly in a boarding house on Hudson Street. By then, Burr was in his mid-50s, and the city he returned to was changing fast. The war of 1812 was reshaping American politics, and the founding generation was passing into history.

Still, Burr showed flashes of the charm and arrogance that had once made him a force in American life. He took on a few legal clients and tried to engage with young lawyers and political operatives, though most were wary. He was deeply in debt, reduced to borrowing from former protégés and selling off books and clothing.

Yet, he retained an unwavering belief in his own destiny.

A Scandalous Marriage and Final Years

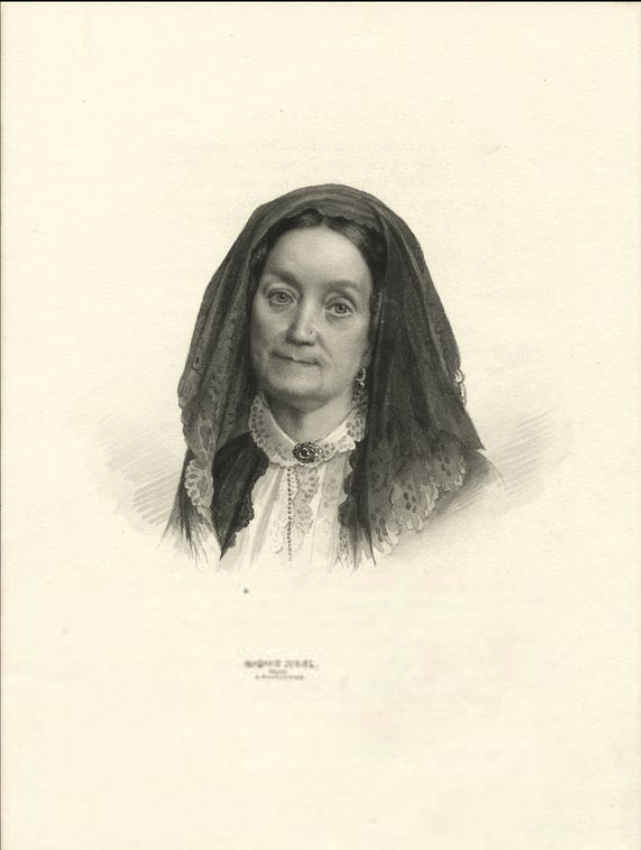

In 1833, at the age of 77, Burr married Eliza Jumel, one of the wealthiest widows in New York City. She owned the mansion that would later become a Revolutionary War museum in Upper Manhattan (today known as the Morris-Jumel Mansion). The marriage quickly devolved into a disaster. Burr reportedly tried to take control of her estate, and she filed for divorce less than a year later—on the very day Burr died.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. (1801 – 1886). Madame Jumel Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ccacb720-c60c-012f-41d5-58d385a7bc34

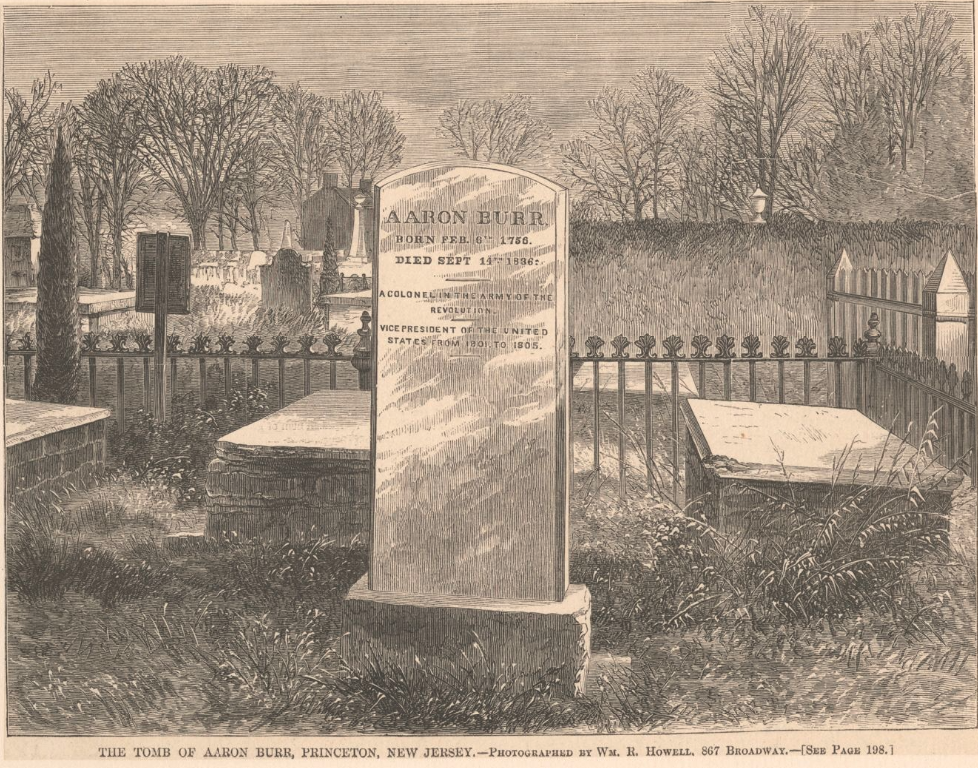

He spent his final years living in a modest rooming house on Staten Island, financially ruined, physically broken, but intellectually sharp. He continued to write letters and entertain visitors who were curious about his storied past. By the time he died in 1836, nearly all his contemporaries were gone. He was buried near his father and grandfather (both presidents of Princeton) in Princeton, New Jersey—his final tie to the world of ambition and legacy that had long since passed him by.

Legacy: A Cautionary Tale and a Puzzle

Aaron Burr’s post-duel life in New York City is a case study in how fame turns to infamy, how brilliance can be undone by ambition, and how public memory is shaped by actions and the stories told about them.

To many of his fellow New Yorkers, Burr became a cautionary tale—a man who had it all, lost it through pride and miscalculation, and spent his last decades walking among the same people who had once feared and admired him, now unseen and largely unwelcomed.

Yet to others, Burr remains a more ambiguous figure: a progressive thinker in law and politics, an early advocate for women’s education and anti-slavery in his writings, and a man ahead of his time in ways that were both inspiring and dangerous.

His name still echoes in the streets of New York—not in monuments, but in the whispered footnotes of history, where the city’s most complex characters tend to live.