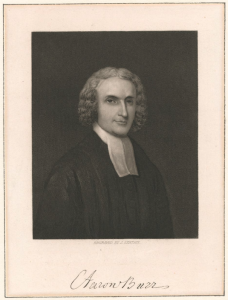

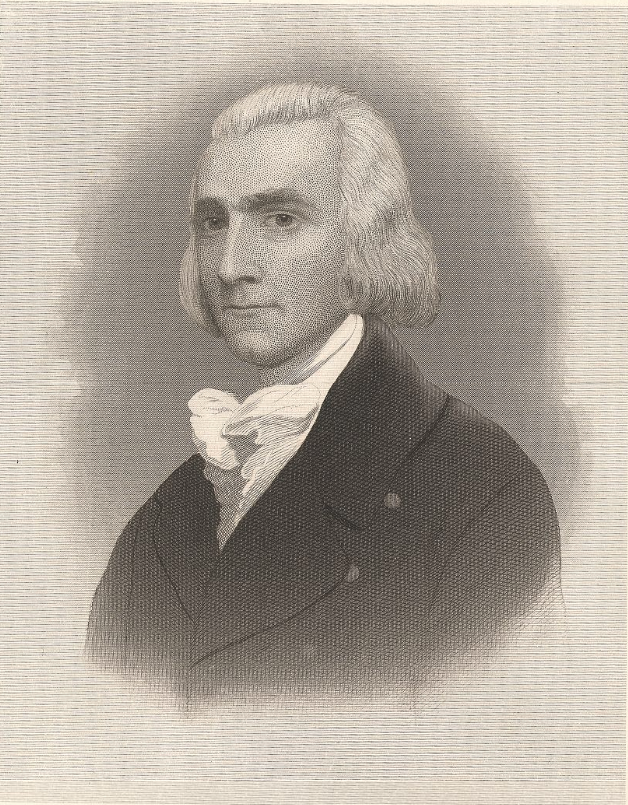

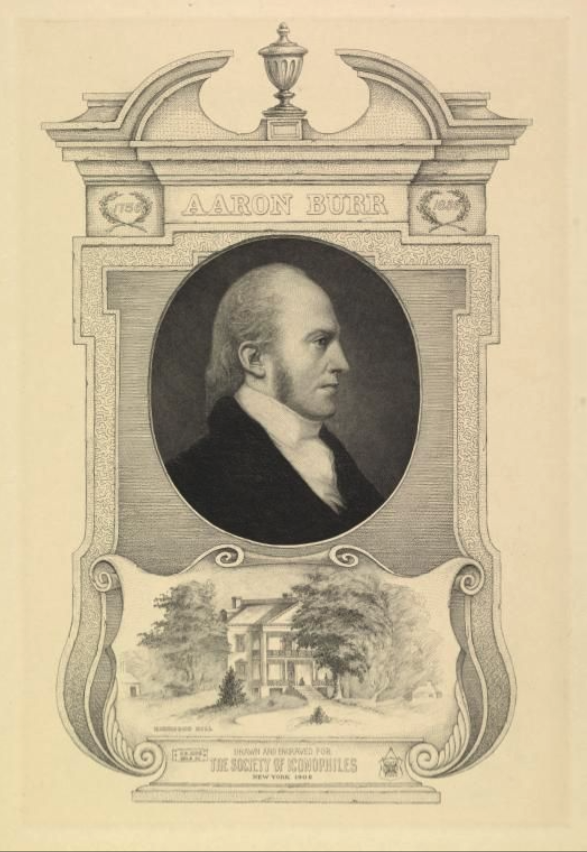

Tucked away on Barrow Street in Manhattan’s historic Greenwich Village lies one of New York City’s most mysterious restaurants: One If By Land, Two If By Sea. But behind its candlelit ambiance and colonial charm is a deep and complex history that stretches back to the Revolutionary era. The building was once a carriage house belonging to Aaron Burr, the controversial third Vice President of the United States.

Today, the restaurant operates out of Aaron Burr’s relocated carriage house, with ties to Richmond Hill, a once-grand estate that played a central role in early American history.

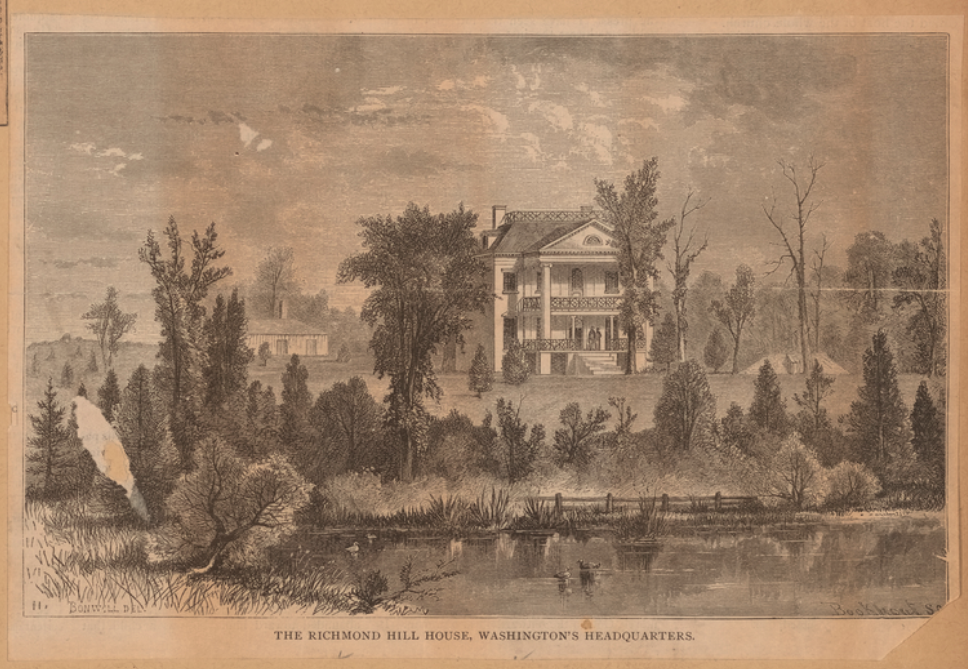

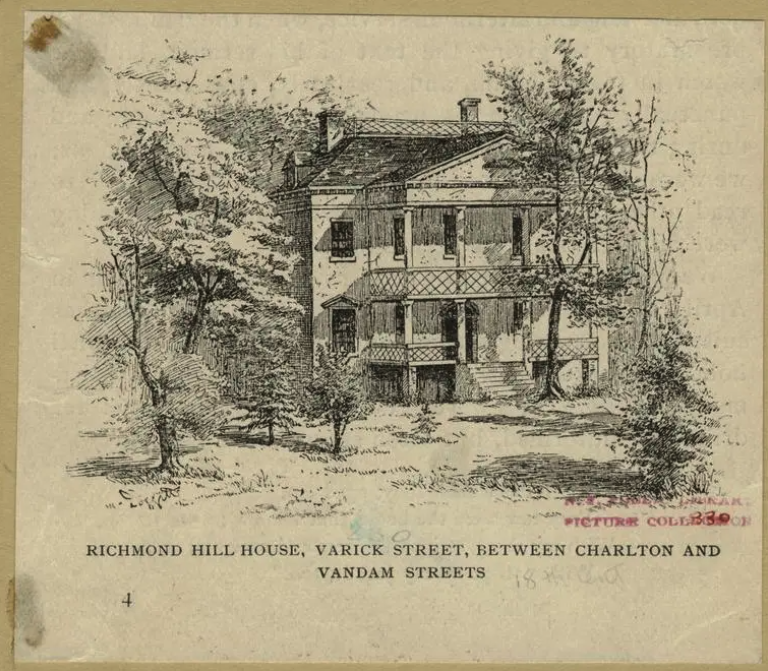

Richmond Hill and the Origins of the Carriage House

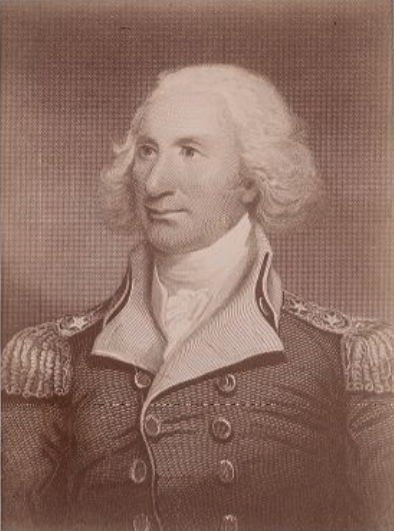

The original Richmond Hill estate was located atop a rise in what is now SoHo, bounded roughly by present-day Varick, Charlton, and Vandam Streets. Originally built in 1767, the mansion became the headquarters of George Washington during the Revolutionary War and later served as the official residence for Vice President John Adams.

In the late 1790s, the estate was acquired by Aaron Burr, who used it both as his home and as a symbol of his rising political stature. However, the stables and carriage house for the Richmond Hill estate were not located directly next to the mansion. Instead, they were positioned downslope, nearer to the Hudson River around present-day Barrow Street, to keep the main house free from the noise and odors of livestock and to align with the street proper. This location was practical and common for the time, especially in hilly terrain like Manhattan’s pre-grid landscape.

Geographic and Historical Context

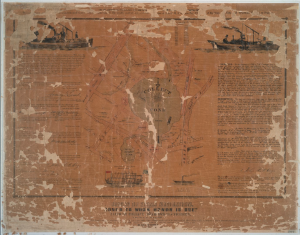

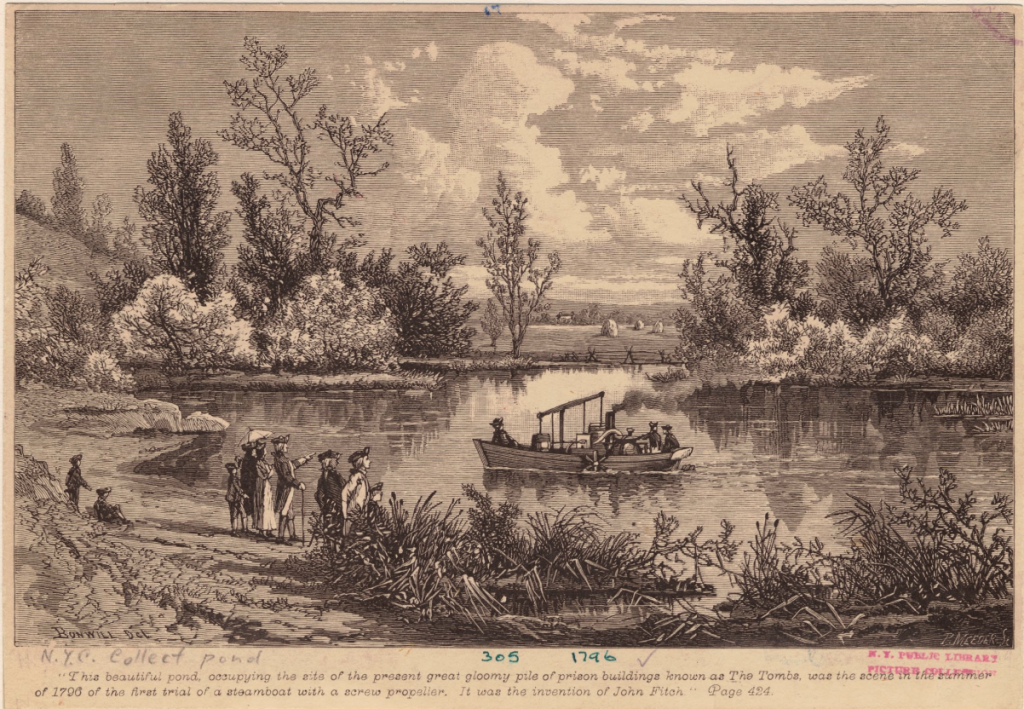

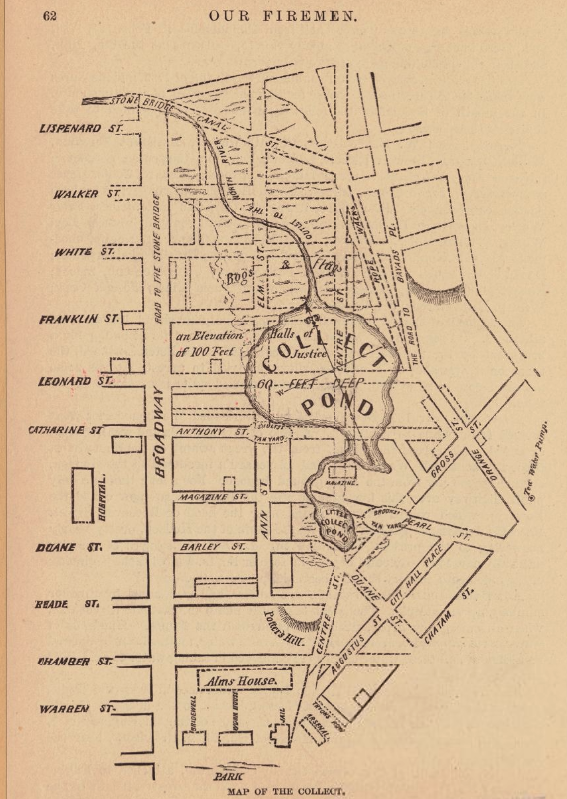

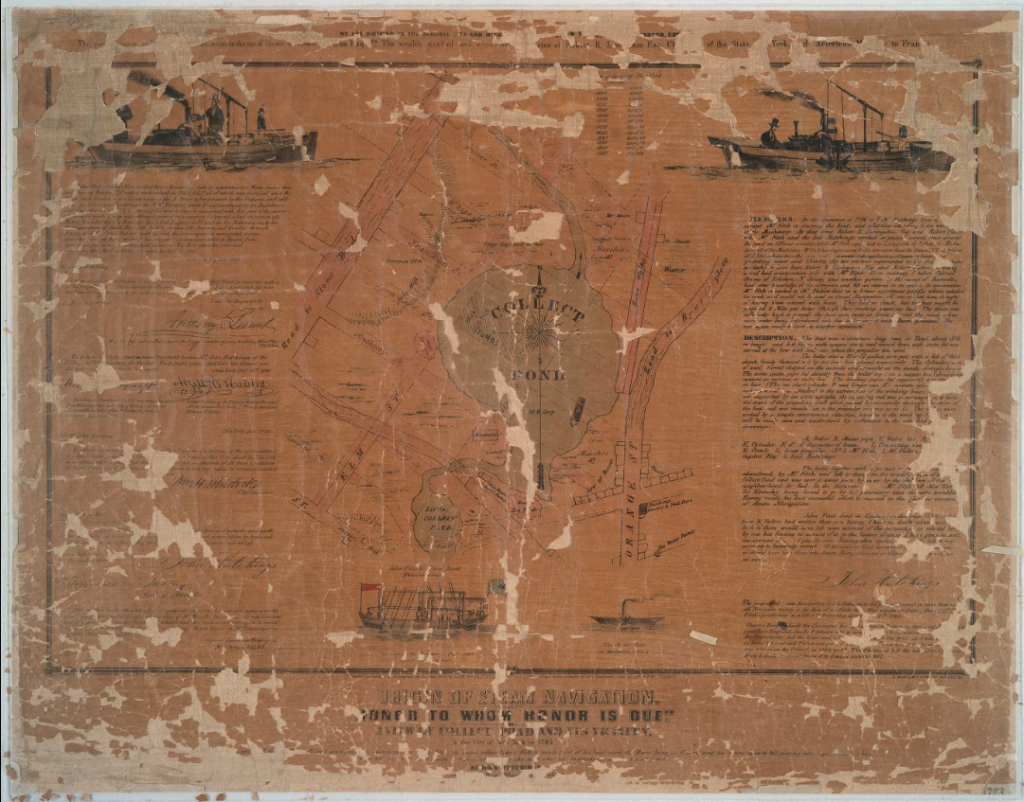

At the time, 6th Avenue didn’t exist as we know it. In fact, much of what is now SoHo and the West Village was marshland. A large body of water known as Collect Pond dominated the area until around 1810, when Canal Street was constructed to drain it. The Hudson River shoreline at the time extended to Greenwich Street, meaning everything west of that is built on landfill, much of which was later filled in by the Astors and Vanderbilts using stone brought from upstate. Burr skated across this pond to his law office on MacDougal Street.

Historical overlays based on early 19th-century maps show that the carriage house and slave quarters originally stood about 200 yards southwest of their present location, which position them on Barrow Street (previously “Reason Street” and then “Raisin Street”). These overlays were once held at the restaurant, but were reportedly discarded during an ownership change. However, related documents are said to exist in the Astor family papers, housed in the New York Public Library (NYPL), including property tax maps and documentation supporting the building’s relocation. The two buildings were joined by a sloping connecting roof in the 1970s, but the barn’s roof was removed for a water tower.

The papers were maintained by “Mrs. William Astor,” William Astor Jr.’s wife. They had five children, including John Jacob Astor IV, who died on the Titanic. She was the matriarch of the Astor family.

Relocation of the Carriage House

When John Jacob Astor and his family acquired the Richmond Hill property in the early 19th century, they began subdividing and developing the land, eventually creating the grid system that defines Manhattan today. As part of this transformation, the carriage house was moved approximately 300 yards to its current location at 17 Barrow Street, closer to the riverfront. The structure that stands today includes original elements of the building believed to be associated with Burr’s estate.

Burr, Smuggling Tunnels, and Local Lore

Local legend—partially supported by historical documents—suggests that the area around the carriage house was laced with smuggling tunnels leading toward the Hudson River. These tunnels, likely constructed in the 18th century, may have originally been used to smuggle prize money and goods seized by privateers operating under the Royal Navy. During and after the Revolutionary War, these tunnels were repurposed by unsanctioned traders and abolitionists, and used as part of the Underground Railroad. The NYC Slave Police raided the premises and killed one of the fugitive slaves being smuggled out in the late 1840s.

Though much of this network has been sealed or destroyed, remnants are believed to exist under buildings along Barrow and Commerce Streets. These subterranean passages added to the area’s mystique and helped fuel ghost stories and lore surrounding the restaurant.

The Carriage House’s Role in American History

Aaron Burr wasn’t the only prominent figure to use the stables. It’s believed that George Washington’s aides-de-camp, including Philip Schuyler (Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law), also kept horses there during the war. The barn could accommodate up to nine horses, and included a covered area to protect carriages from the elements.

One particularly notable artifact—a sleigh bearing Burr’s Vice Presidential coat of arms—was found at an estate auction in Pennsylvania and once sat in the restaurant’s garden, though its current whereabouts are unknown.

From Historic Carriage House to Iconic Restaurant

By the 20th century, the building had fallen into private hands. In the 1970s, it was converted into the restaurant One If By Land, Two If By Sea, named after the famous lantern signal used by Paul Revere during his midnight ride. The building was restored, and its rich history was embraced as part of its charm.

During the early 1990s, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, then a member of the board of the NYPL and a preservation advocate known for helping save Grand Central Terminal, was involved in efforts to research and preserve elements of the building’s past.

A Living Monument

Today, diners at One If By Land, Two If By Sea might be unaware that they’re seated in a building with ties to one of the most infamous figures in American history. The restaurant is a living monument to New York’s layered, complex past: from smuggling tunnels and slave quarters to vice presidential sleighs and shifting city shores.

Sources

- New York Public Library Maps Division

- Astor Family Papers (NYPL Archives)

- “Historic Homes and Institutions and Genealogical and Personal Memoirs of New York” (1907)

- NYC Department of Records and Information Services

- Museum of the City of New York

- One If By Land, Two If By Sea

- National Register of Historic Places

- Greenwich Village Historic District Designation Report